Can Sungu "B Replaying Home", 2013

Before the invention of "cheap flights", cars were the most important means of long-distance travel for Turkish guest workers (Gastarbeiter) living in Germany. The train was slow making the journey on rails very time consuming. Flights on the other hand were mostly unaffordable but they also had luggage restrictions, which made it nearly impossible for the travellers to carry all the bayram[i] presents they wanted to give their relatives at home. So finally the opportunity to show off a brand new German car, and the relief that luggage was restricted only by fatherbs packing skills made the trips by car even more attractive. In the trunk many bfirstb items were carried from Germany to Turkey: deodorants, soap, radios, binoculars, colour TVbs...amp; Every new commodity which they brought along with them from Germany provided great attraction and strengthened positive clichés about German technology and Occidental opinions about the higher development of German and/or Western culture. The almost hysterical desire for Western consumer products resulted in such a craze that even people without any relatives abroad now wished to own one of these products. Due to high tariffs and inadequate mass purchasing power during the 1980s in Turkey, electronics in particular labelled "made in Germany" were regarded as luxuries. Therefore, everything that did not fit into fatherbs car was now transported by pickup truck. In addition to this, groups of guest workers that regularly travelled to Turkey in the early 1980s, unintentionally established a smuggling route which eventually evolved into a bsilk roadb for professional smugglers.

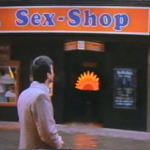

Video tape recorders, which have been the most significant of these smuggled products, gave way to a new cultural field in Turkey: video. But in order to understand the how video culture developed in Turkey, we have to go back to the starting point, namely to Germany. In the early 1980s, first Betamax and then VHS video recorders had become widespread in Germany and in a very short time they were also well accepted by many Turks. The lack of sufficient German language skills, as well as the fact that the content of German television broadcasting was not targeting the Turkish audience at all, led Turkish immigrants increasingly to rent videotapes. Somehow in this context watching videos replaced watching German television. These video nights were a sort of social event including neighbours and family. Watching videos was accepted as a pleasant and family-friendly alternative to going out and getting attached to German-dominated cultural life.

The enthusiasm for video inspired Turkish film producers to export Turkish movies to Germany and transfer them to videotape. In order to take part in that growing market, a lot of Turkish video companies opened up in Germany. These companies had their own studios and were responsible for the transfer of imported movies to videotape. Usually they enriched the content of these videotapes with commercials and trailers.. They packaged and distributed the tapes to Turkish video rental shops in German cities. Some of these studios also produced low-budget video movies by themselves targeting the Turkish audience in Germany.[ii]

Those who spent their summer vacations in Turkey now started to bring video recorders and videotapes along with them. In Turkey the idea that you could watch any movie any time you wanted was magical. The video recorders were mostly combined with colour TVs which were also brought by relatives in Germany and which were placed in the favourite corner of the living room. The copyright laws in Turkey could not keep up with technological innovation and the Turkish state did not enact laws against the illegal duplication of videotapes. Thus, a new video market rapidly grew in Turkey, which in its early stages was a bit improvised and "semi-legal" as it was dominated by duplicated or smuggled videotapes. Video clubs, where videotapes could be rented and/or duplicated at favourable prices, became commonplace. Some Turkish film distributors in Germany were keen on these developments in Turkey and got involved in smuggling video recorders. The smuggled goods were sold, for example, in a big warehouse in Istanbul called Dogubank, a place admired by Turkish consumers due to its low (tax-free) prices. Dogubank still exists and is a popular spot for buying home appliances and electronics.

For Replaying Home, I started my research in 2010, a couple of years after I had moved to Berlin. At this time I had already heard of some of these movies. A few of them I had even watched before. But the real turning point of my interest and the start of my research occurred when I coincidently discovered one of the last Turkish video rentals in Berlin. The shop was about to close and the owner had decided to make a sell-off. I took the opportunity to buy some videotapes and I talked with the owner as well. As a result of him sharing his memories with me I learned a lot about the golden age of home video. This was the trigger for a long research phase, during which I watched a vast number of movies, tried to reach local experts and collected more and more information about production companies, directors, actors and so on. I noticed that most of these movies were based on similar plots that, following their protagonist(s), focused on the life of Turkish immigrants in Germany. The plots mainly deal with issues such as culture shock, homesickness, discrimination and the threat of assimilation, and discuss them from ranging perspectives related to religion, national identity or social rights. I began to edit sequences into thematically titled clusters, for example "arrival to Germany", "first impressions", "Neo-Nazis" or "drugs". I created a new narrative imitating the narratives of the movies by editing cuts, taken from more than 25 movies, into one plot. I tried to avoid documentary approaches and I left out any anthropological statements. In contrast, I explicitly wanted to emphasize fiction and the storytelling.

The installation Replaying Home recreates the bvideo cornerb of an anonymous Turkish family and presents therein this found footage-video. The video includes selected cuts from smuggled videotapes such as the Turkish movies shot in Germany during the 1970s and 1980s, commercial films of German-based Turkish video studios, movie trailers and title animations. The installation offers a one-on-one experience, where the visitorbs role shifts between spectator and family guest. Replaying Home invites the viewer on a journey through a fictive universe based on stereotypes, Occidentalism and the traumas of migrant life.

[i] Religous feasts of Muslims.

[ii] Due to digital revolution, these companies were not able compete against digital TV and online videos and closed one after another. Some of the movies which were only released on videotapes, are now in danger of disappearing forever.

***

Can Sungu was born in Istanbul, Turkey, studied Film (BA) and Visual Communication Design (MFA) at Istanbul Bilgi University and at the Institute for Art in Context in Berlin University of Arts (MA),B gave courses on film and video production, facilitated workshops and took part in various exhibitions in Europe, such as at transmediale'14 and Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Rijeka. He founded the non-profit association bi'bak e.V and the project space bi'bak in Berlin-Wedding. Within a transdisciplinary practice, he experiments with diverse forms of media like photography, film, video, animation and interactive media. His works mostly deal with issues like migration, mobilities, consumer society and their aesthetic dimensions. His critical approach concentrates on fields where popular culture and various concepts such as kitsch, tourism, ideology, mass media and urbanization meet. By attaching great importance to humour and provocation, he incorporates interactivity and participation into his creative processes. Can Sungu is based in Berlin and Istanbul.